From Russia with love, LEVS in Rusland

- 01 November 2019

- By Marianne Loof

That we work in Russia is partly a coincidence, but that we have turned this into success is not. Curiosity was of course the first reason to respond to the question of an ambitious developer, who mainly focused on affordable housing. But curiosity soon turned into commitment to the task in Russian cities, where high construction output is accompanied by a lack of vision on spatial planning, urban design and architecture. Our Dutch tradition in the field of integrated spatial design and LEVS' expertise in designing compact urbanity with affordable housing provided a fruitful starting point for a now seven-year romance.

In the five years that we have worked in Russia, we have become fascinated by the country, but also by the people and companies with whom we work. Companies that are open to new ideas, that are looking for opportunities and knowledge. People who want to understand how they can create a living environment that they value so much in Europe and especially in the Netherlands. And it is up to us to analyze and combine those Dutch values with the Russian soul and an unapproachable climate. The complex and layered Russian society is fascinating and you cannot understand without seeing the tragedy.

For us in the west, Russia, the immense country in the east of the European continent, has always been 'far away'. We have never succeeded in bringing our worlds closer together. Last year in Zomergasten, Pieter Waterdrinker characterized Russia's complicated relationship with the West like no other by showing the Russian-Italian feature film Oci ciornie (1987). Marcello Mastroianni is the westerner who first encounters a wall of bureaucracy, only to be received extremely warmly afterwards. According to Waterdrinker, this is because Russians have both fear and desire for the West at the same time. Even in the cities where we now work, it always strikes us: outdoors everyone looks straight ahead and no one shows emotions. But indoors they are Italians: warm, generous and generous, where humor and booze go together.

For us, working in the Russian context does not mean exporting Dutch urban planning and architecture. It is a search for essential characteristics of our Dutch Liveability, as we have come to call them, in order to connect them with the history and culture of cities such as Yekaterinburg, Kazan and Tomsk. This Dutch Liveability is not primarily about aesthetics or architecture. It is a translation of an open society that has been formed with us over centuries.

The need to create a man-made country, with compact cities, led to cooperation in which integral cohesion was indispensable. In the Netherlands this is a historically developed situation: our intimate cities, where you can look in through the windows, and our safe civil society, where the children play in the street. There is a widely supported awareness that joint ambition between government and private parties in area development is necessary to achieve high quality at all levels, from urban development and landscape design to building design, housing plans and public space.

Our first project, Alexander Pond, may not have been built, but it was a flying introduction to Russia. After meeting our client via Skype, we decided to take up the challenge and boarded a plane to Yekaterinburg, a city on the border of Europe and Asia. After flying overnight, we were at a location in the woods, where we realized that the assignment was not for a building block, but for a neighborhood with almost 2,200 homes.

This first trial was in many ways a steep learning curve of do's and don'ts: regulatory, with complicated and demanding Russian soling requirements; in the field of residential culture, in which living on the ground floor is considered extremely dangerous and unattractive; but also in the field of collaboration, with long workshops in which our loose and open communication style contrasted with the hierarchical Russian corporate culture. And in the culinary field, we quickly learned that our Russian guests in Amsterdam did not like to have sandwiches for lunch and that a warm lunch was really necessary, preferably Italian.

Fortunately, we were able to use a lot of the insights and knowledge gained in our second project Sukhodolskaya that was completed. The neighborhood's namesake, Sukhodolsky was a nineteenth-century painter of romantic landscapes. However, the plot itself was completely bare and without context. We decided to turn this planning strategy, often missing in Russia, to our advantage by creating a closed and small-scale inner world within an eerie outside world, with the paintings by Sukhodolsky and the communal courtyard garden of Van Loghem in Haarlem as green inspiration. After the first block was delivered, we received a touching email from his granddaughter who somehow found the plan and the reference to her grandfather.

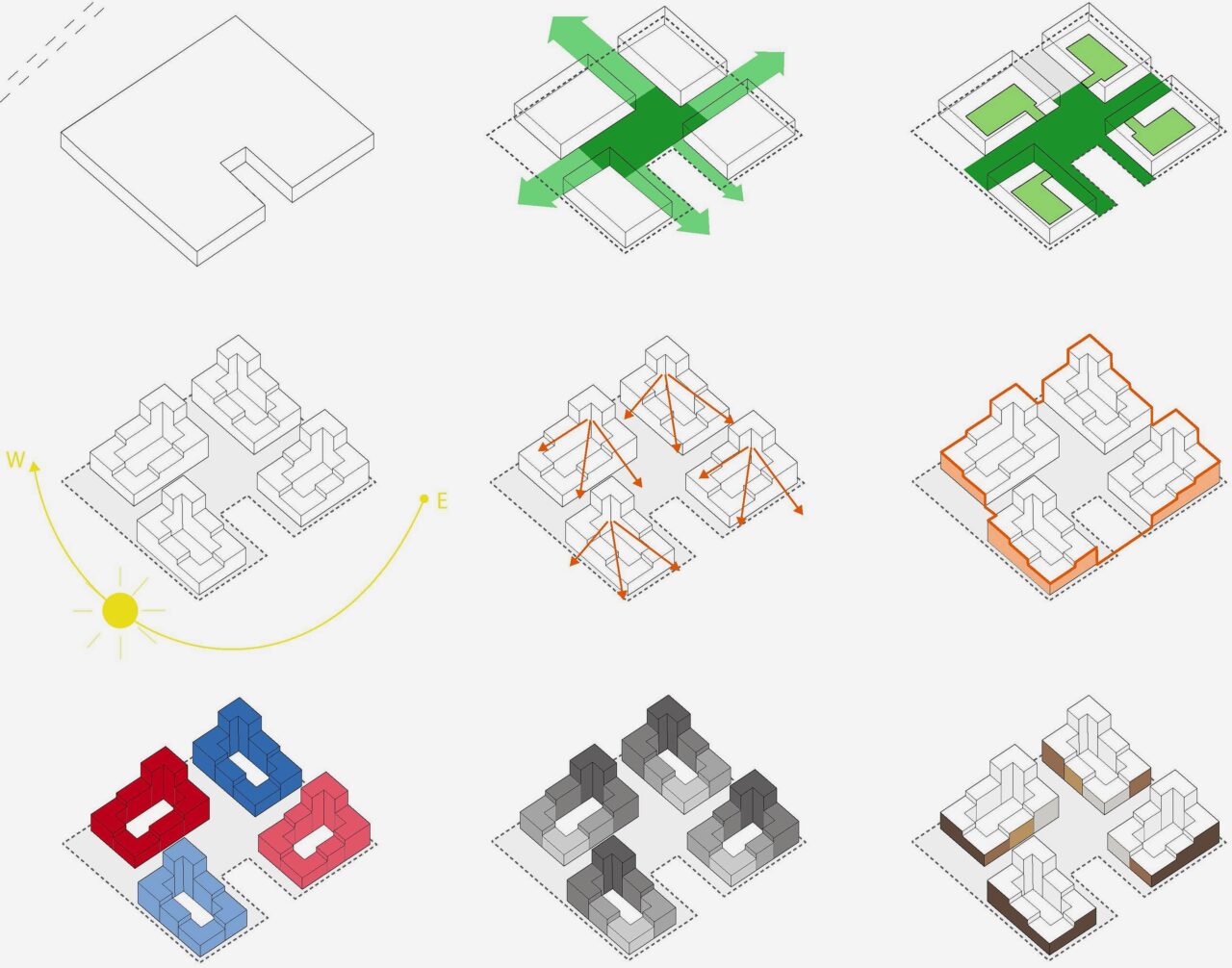

We had also learned a lot about the exceptional insolation rules. According to these rules, depending on the region (and in the case of larger houses even in several rooms), each home must have at least between one and a half and two and a half hours of direct sunlight, calculated on the actual latitude and longitude of the location. In the Siberian context this is no mean feat and an explanation for the large distances that are often used for convenience between buildings. With our Dutch belief that 'rules are there to be beaten', the blocks are exactly shaped in height to the necessary insolation. This forms the silhouette of the fortress that is Sukhodolskaya on the outside, a hard shell that encloses a sheltered, intimate and green interior.

Although we were not an urban planning agency pur sang in the Netherlands, we suddenly received an invitation for a closed competition for housing on an area of 180 hectares in Kazan. And meanwhile infected with the Russia virus, we decided to take up this challenge.

In any case, the first, fully organized, meeting in Kazan seemed like a great opportunity to discover this completely different area in Russia. Because, that much was clear by now, the great Russia has a fascinating variety of cities and cultures. Kazan is the capital of Tatarstan, a republic within the Russian Federation, 150 years older than Moscow and home to Volga Tatars, whose origins are said to date back to Genghis Khan.

To our own surprise, we were selected for the second round. In a 'dialogue model' we traveled to Kazan several times in the following months to work on the plan in workshops with the Tatar client. During a workshop three days before Christmas, not an important time of the year for Russians, an intercultural Christmas dinner was organized, full of Tatar delicacies, combined with local specialties from the Dutch, British and Spanish designers. While toasting with Dutch Bols jenever, Spanish wine and English gin, world peace was easily settled.

Our winning plan, Machaon Valley, set itself apart from our Anglo-Spanish competitors by taking the existing village as the logical starting point for the expansion. The street pattern is organically shaped to the sloping landscape, explicit and not orthogonal. Mixing functions instead of isolating them, as is usual in Russian cities, can create a vibrant community. The old, dry riverbed with small lakes, so typical of the Tatar landscape, can thus be preserved and transformed into a natural park.

We now work in Russia from Moscow to Tomsk. Yet Yekaterinburg, incidentally an 'open-air museum' of constructivist architecture, is our second home. Here we are now working on several challenging plans, such as Solnechniy and Stachek. Our largest construction project, Forum City, is under construction in the center of the city, which incidentally was designed as a grid city by Dutch-German engineers at the end of the nineteenth century. The city has developed strongly since the 1990s: a multitude of styles, shapes and uncontrolled building projects now threaten the original clear structure of the city.

For this assignment, the client's initial question was which 'architectural style' LEVS offered. If we could send pictures of that. But even now we decided to get on the plane and get acquainted. Three plans had already been drawn up for the large open location in the city, but the development was unsuccessful. Our answer was apparently simple: architectural style was not the real question at all, it was based on our conviction about identity and living concept. There is also a new target group in Russian cities that needs a metropolitan lifestyle. Forum City is becoming a small city in a big city. On the one hand, it is a building block that repairs the historical grid structure of the city and refers to the old brick buildings of the old Yekaterinburg, but at the same time embraces the new, multi-shaped city. Forum City's site was once the city's open market square. This was the inspiration for a modern concept of a market hall in the passage between the new building and the existing gallery.

The dream and vision of Forum City have been presented by us on one A4 sheet. The plan was immediately embraced and, despite many risks, obstacles and, of course, setbacks in the implementation, it is being implemented. Every six weeks we are there on construction, in all seasons and with temperatures between -30 and +30 degrees. These temperatures are actually a metaphor for the Russian reality, where the conditions are extreme and the obstacles numerous. The perfect society is not a self-evident 'right' here, as in the Netherlands. In Russia, it can and must be made by people who take risks, who dare to stick their necks out. The added value of us as architects is greater than in the Netherlands. Working in Russia is complex and demanding, but at the same time it is much more than just an adventure. The romance has since become a deep love.