The new urbanization

- 01 November 2019

- By Adriaan Mout

The housing task changes over time and we as a professional group change with it. The construction of Vinex neighborhoods has had a definitive end since 2005 and the urbanization of the existing city seems unstoppable at the moment. After a severe dip due to the crisis, all brakes seem off and the Dutch city is being redefined. Density is increasing and so are the buildings. Every self-respecting city now has a high-rise vision in which ever higher towers will determine inner city building. The skyline within our office is also changing: Styrofoam towers form the horizon from our workplaces.

This leads to discussions inside and outside the office about how our Dutch cities can accommodate the new high-rise buildings and densification. But also to the question of what living in towers means for the residents and for the city.

In our country, half a million homes were added in urban areas in the period between 2000 and 2015, and another 700,000 homes must be added by 2030. If we want to keep the green space between the cities open, we can only do so with massive densification within the cities. But the Netherlands is not a country of metropolises: we have nice small cities, such as Leiden, Haarlem, Utrecht and The Hague. We must cherish our cities and further densify them, and towers can contribute to that. Towers can also provide an answer to the demand for a new form of urban hedonistic living for new target groups, which we have not served so far. But these high-rise buildings must be a part of well-considered urban planning visions, innovative housing concepts and an integrated approach. This is no easy task.

In 2008, we were invited to participate in an architectural competition in Den Bosch for a block in the Paleiskwartier plan. This plan was by then already twenty years old. It was unique in its size and because of its central location: directly behind the station and against the city center. We held the presentation in September 2008. One week later, Lehman Brothers in New York collapsed and we were at the beginning of a crisis that, certainly for construction, would have a huge and long-lasting impact. There was no result of the selection and, especially given the scale of this project, that was not surprising. It wasn't until four years later, in 2012, that we received word that we had won the selection. And not only that, the task had in the meantime become more than twice as large and the density correspondingly so. The increase in density and the reduction in average dwelling size were the prelude to what the post-crisis housing challenge would become. In this plan this led to an interesting mix of access typologies, but also to the challenge of making good one-sided housing on the inside of a closed block. It became a search for proportions, profiles and heights that led to densities we had not thought possible. Still in the aftermath of the crisis, we transformed the plan in a construction-team into an urban building block with allure and almost three hundred fine homes. By 2017, the plan had finally been implemented in its entirety. The crisis has had a purifying effect here.

The plan to turn Amsterdam's Zuidas into a mixed residential-work area already dates back to well before the crisis. Yet it took a long time for the Gershwin strip, the envisioned housing development behind the back of the offices located along the ring road, to be developed. The direction of this development was of Amsterdam precision. Complex building envelopes with almost impossible to follow formulas had to ensure the intended density and metropolitan character. Well-considered urban planning in conjunction with good architecture, a combination that has made Amsterdam great.

In 2013, we won the architect selection for the westernmost lots of the strip. From the complicated plot rules, we composed the Gershwin Brothers George and Ira, two residential buildings on a commercial plinth that sit on a two-story parking garage. It is precisely these complicated rules that led to an attractive plan: a strip of sculptural buildings and an ingenious alternation of spaces, attractive greenery and special functions at ground level. A small piece of the city has been created as the city should be, with fine and comfortable homes. In 2018 our project was finished, after a careful process with a pleasant and committed client, who had a little something still in store for us. Suddenly, artist Jeroen Henneman appeared on the scene, sketching on the construction signs for his artwork De Doos (The Box), which was trying to find an appropriate position on the building. That work of art was of course placed at the highest point of the building, a true feat, because of course this had not been taken into account. A 2D work of art with 3D depth - architects can learn a lot from this!

In 2018, we were asked to tender for a very tall tower in the Binckhorst in The Hague, an industrial area that is being transformed into a high-density residential and commercial district. The question of how this could be realized with high-rise buildings created a new densification challenge for the city. This was also the moment that the residential tower seemed to have made its definitive breakthrough in the Netherlands. At the same time, the proponents and opponents of towers tumbled over each other. In the Sluis neighbourhood discussion in Amsterdam, for example, a truly substantive discussion between peers, led by Sjoerd Soeters, finally flared up again. High densities lead to unrest and stress, tall buildings bring about a greater sense of bustle and anonymity, and moreover the connection with the street and public space is lost, was his motto. Many architects also asked themselves how to make towers attractive to families and how to compensate for the lack of greenery. In response, new experiments were developed, stacked cauliflower neighborhoods with residential areas, family scrapers and forest towers. For now, the initiatives remain mostly limited to plans on paper.

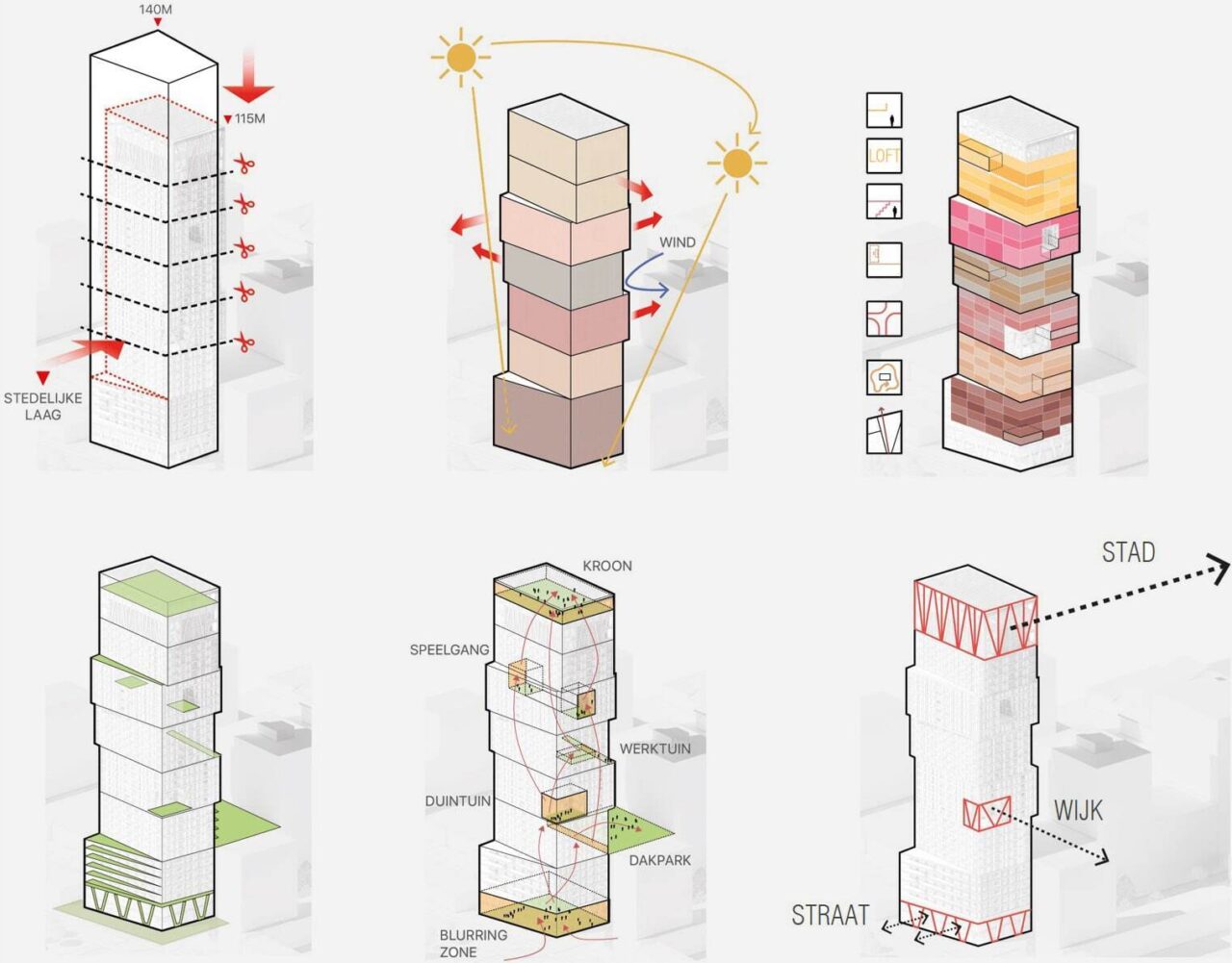

Thus, the assignment for the tender in The Hague already tentatively anticipated a new view of living in tall buildings and high densities. Our approach went a big step further in defining solutions for the new densification. In doing so, we won the tender for a tower that could be up to 140 meters high. In this plan, Binck Blocks, we literally stack neighborhoods with countable quantities of housing, with their own identity and a characteristic common place per neighborhood and a wide variety of housing types. We do this for a mix of residents who, just like in a flat city, regardless of age or family composition, can identify with their neighborhood.

That this need not be at the expense of the demand that was implicit here to make an iconic building is proven here. The stacked boxes with large steel profiles refer to the industrial past of this location and mark the new Binckhorst from a great distance away. The task of truly green and nature-inclusive construction is a difficult one. Often enough, plans for green towers fail to live up to the image of beautiful renders. At Binck Blocks we developed a well thought out and promising strategy. The starting point is the natural symbiosis between nature and the city, which creates opportunities for a new layout in which ecological cycles are formed. These opportunities are exploited here by providing space for flora and fauna in the collective spaces, facades and on the balconies. For biodiversity, the building is considered an ecosystem and biodiversity hub. Birds, butterflies and insects nest in green shelters.

This tower in The Hague is part of a series of plans for towers under development in this city. The tradition of careful spatial planning seems to have been abandoned and the control of urban space left largely to the market. There are general policy guidelines and visions for high-rise in the city. But well-considered urban planning, as in the Paleiskwartier and Gershwin, but also as in the Sluisbuurt in Amsterdam, has been replaced here by something that looks more like uncontrolled growth. And The Hague is not the only city that, obsessed with the task of adding numbers, seems to be giving the market free rein.

For us, the essence of the high-rise assignment is to find solutions to counteract the anonymity of this form of housing and to ensure that the towers actually connect to the location where they stand. This requires an understanding of the complexity of the city. Only then can you translate changing urban functions and lifestyles into relevant area concepts and new types of (residential) buildings, including towers. Housing is no longer exclusively about living; there are more and more mixed forms of functions. Homes are becoming smaller and living arrangements are changing.

Globally, there is a great challenge for cities. Demographic changes and transitions demand much from the future city. Only if cities continue to reinvent themselves will they remain a welcoming place for people. That is the challenge with the projects that we, as an office, are increasingly confronted with and in which we are always looking for the essence of the project and the uniqueness of the place: home is where the heart is.