Why LEVS loves Africa

- 01 November 2019

- By Jurriaan van Stigt

Our relationship with Mali has a very long history and is intertwined with LEVS in many ways, through architecture, humanism, anthropology, art, and thinking about realizing a connected society.

We studied in Delft in the 1980s, on the fault line of a number of architectural views. After 1970, the predominant view was held by a number of architects from the Forum movement, by Van Eyck, Hertzberger and Bakema, but also by anthropologist Hardy and structuralists like Apon. The idealistic idea of the makeable society from the 1960s was overtaken in 1980 by the reality of partially impoverished cities, migration to satellite towns, housing shortages, speculation, vacancy rates and squatters' riots. A new rebellious generation of students and teachers in Delft was tired of Hertzberger's hermetic good-fault thinking and milk-bottle-next-door stories, and wanted to place the design tasks in a somewhat broader perspective. Key figures from Delft, such as Weeber, Risselada, Bollery, Von Moos and Tzonis, were involved in design studios that introduced new working methods, were socially involved and looked at all the tasks from a socially critical angle. Serious research into housing typology began. Stacks, links and living environments were sorted, ordered and recombined. The famous 'plan suitcase' of the plan designed by Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA) for IJplein in Amsterdam seamlessly blended with the plan folders and plan documentation produced in Delft, which can still be found in all the bookcases of our contemporaries. All of this formed the foundation of the solid housing knowledge and fascination of the Dutch generation of architects educated at the time.

Perhaps the wide stream of topics and perspectives that typified this period created confusion and less clarity about the direction in our profession, but it also gave a lot of room to look at the profession with an open mind. Looking back now, we see the value of publications in the journal Forum, in a period when The Story of Another Thought, as first put into words by Aldo van Eyck in 1959, was the central theme. Therein, if you take a broader view, you can find the subjects that now play an important role in our work: modernity, historical awareness and the social-sociological and contextual connections. Living and the city are our main field of work: the diversity of the city in which living, working and residing are central, but especially the making of connections between living, the street and the square.

And so we end up in Mali, with the Dogon, a people who play an important role in this thought process. In 1967 an article in Forum magazine, Dogon: basket-house-village-world, written by Aldo van Eyck in collaboration with two anthropologists, described a visit to a Malian village. 'The village is my home,' says one of the villagers. The Dogon do not talk about their house as a separate object, but about the village, the community and the place of everyone in that community. This inspired to think about meeting, working, transitions between public and private, between inside and outside, about the size and scale of everything that was built and how you can relate to that as a person; things that had been lost from sight in the 1950s and 1960s. Many architects, artists, writers and photographers went to Mali, not only to hear the stories, but also to see the wonderful clay architecture of the Dogon and, of course, the architecture of the equally special Djenné.

And so in 1981 I left for Mali together with Herman Haan and my father Joop van Stigt. I ended up staying there for almost three months. By living among the beautiful people and the clay architecture, the stories from Forum came to life. Repairing and realizing two dams and measuring a rock, on which an ultimately unrealized museum designed by the fascinating storyteller Herman Haan would be built, were the beginning of a long association with Mali. After that, of course, I continued my studies in Delft, but it was my father who continued to visit Mali and started the Dogon Education Foundation (SDO) in 1995, with the aim of realizing schools and wells. In the period from 1995 to 2011, numerous projects were carried out. As of 2009, we, LEVS, started to actively support the foundation, but at the same time transform it. Meanwhile, the foundation has a more holistic approach, in which regional and integral development are central, with themes such as education, training, women's groups, agriculture, desertification, water, health and culture. The foundation now has its own organization in Mali, which is supported by a broad team of volunteers from the Netherlands and is therefore now called Partners Pays-Dogon.

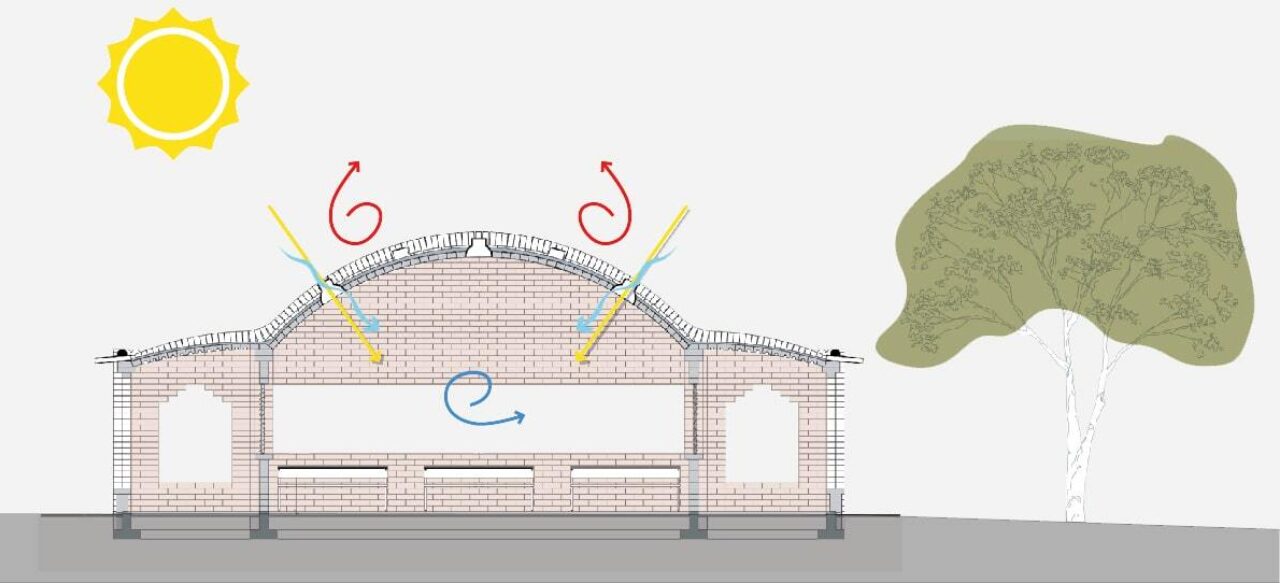

During the post-2009 crisis, it was possible to work with young architects on the Foundation's projects in Mali and to map buildings and construction methods. The resulting booklet, More than Building, illustrated four school construction techniques: traditional mud-brick schools, concrete stone schools, cut stone schools and finally a sustainable modern technique, compressed earth blocks. By 2007, it had become possible to build with this technique, through the purchase of a stone pressing machine. The development of this building method HCEB (hydraulically compressed earth blocks), using locally available raw materials, and the training of local builders became two of the spearheads of our contribution to the foundation.

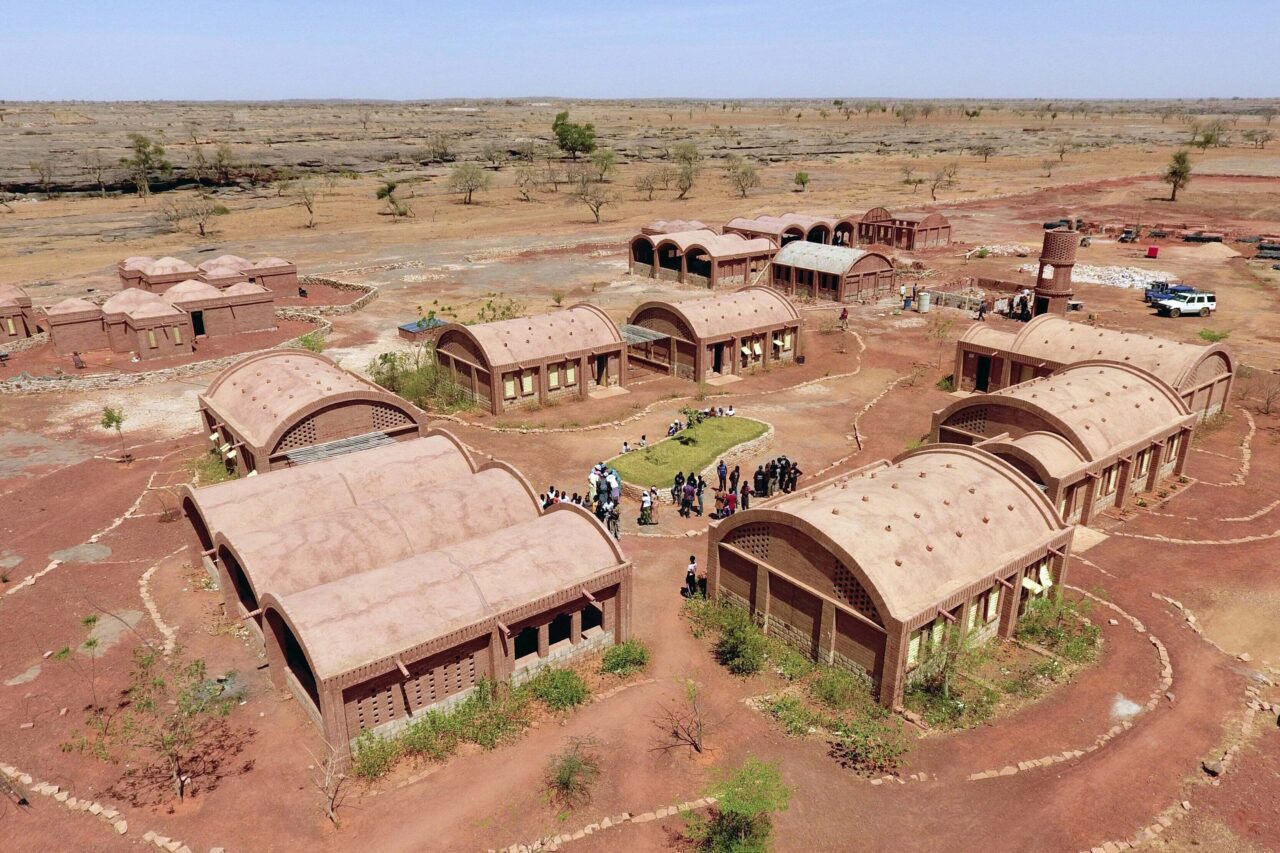

The "village" of Sangha, with forty thousand inhabitants, does not actually exist: it is an amalgam of thirty-seven communities, mostly built on the rocky outcrops of the plateau. The Practical Lyceum is built on the grounds of two communities, the twin villages of Ogol Dah and Ogol Leh, between which the still available land between the rocky outcrops is used for agriculture. On the rock is an amalgam of 'family homes', a square and between the homes occasionally a larger space for the whole village; houses, granaries and family altars arranged in a more intimate scale. The Practical Lyceum in Sangha is designed to gradually and organically grow into a community. It consists of a residential cluster for the teachers, a cluster for the organization of the school and in between and around it a green "garden" with clusters of classrooms and workshops for the different training directions: construction, electricity, water and agriculture. It is not a large imposing structure, but a building with a relatively small scale for this type of school in Mali, a building as a village community that moves with the times. This Practical Lyceum is a first search for a different typology for a school, for special details and for different principles for making load-bearing masonry structures, inspired by local knowledge and skills.

Elementary schools, such as the one we designed in Tanouan Ibi, are almost always solitary, in a place determined by the community. They are used by several villages. It is important to also create a green space, with trees and water, in conjunction with the school, to mark the new place for the community. Increasingly we see that, through the creation of gardens and water, over time extensions of the community develop around the school.

Because there was a lack of knowledge and opportunities to apply the new construction method with masoned, load-bearing structures, it was necessary to realize professional training and projects. This gave rise to a series of designs, including the first residential building. Together with OSKAM v/f, the builder of the brick press machine, we are working to improve the technology and develop new shaped bricks and are now working on a construction manual for teaching in technical schools.

Together with the community we continue to build on the surrounding area. This is where the future challenges for LEVS in Africa lie. In Mauritania, we are working with the government to create homes with schools in rural areas and to set up training centers so that we can build with local youth. In Nigeria, the challenge is even greater: from many organizations and initiatives, the search has started towards developing settlements in suburban and rural areas, together with the local population and focusing on water, agriculture, energy, food supply, education, employment and entrepreneurship. People need to be trained in many areas to make this happen. It takes patience not to draw 'the solution' for a moment, but to actually get something going.

The model of this regional area development in Nigeria has many parallels with the Partners Pays-Dogon foundation's approach. Ultimately, there, in an area where twenty million people are looking for a new home, we will focus on training local builders and helping them to build new communities. Now how to 'design' for this is the real challenge for us in Africa. But remember: 'Africa is not a country.'