Home is where the heart is

- 01 November 2019

- By Marianne Loof

We threw ourselves wholeheartedly into this assignment. Everything was designed: from the entrance gate with a lamp and letterbox to the roof terrace with a pergola and beautiful open staircases, which led to a 7.2-meter wide living room within a spacious floor plan. A project full of inspiration, which was adopted by the residents, and everything still looks beautiful and well cared for almost thirty years later.

The BouwRAI was a precursor to the Vierde Nota Ruimtelijke Ordening Extra (Vinex). Loof & van Stigt, as the firm was called until 2008, realized a considerable number of homes in these Vinex districts. Designing in Vinex nieghborhoods led to discussion within the professional community from the outset. In terms of subject matter, the Vinex design task was not considered to be full. The Row house on a new housing location would not give enough depth to the role of the architect. In the 1980s, this depth was determined by the social component of the design and urban renewal with public participation. Big names like Theo Bosch, but also Dunkirk van der Torre, had developed their practice in this and proved their right to exist. At the same time, a new generation had emerged that, inspired by Rem Koolhaas and Delirious New York, embraced the metropolis and urban design.

Although the Vinex assignment heralded the great heyday of Dutch architecture, but certainly also of the economic growth of many architectural firms, the stamp of "Vinex architectural firm" was not a compliment by a long shot. It was commonplace to maintain a certain mental distance from it. Later, in the Vinex district of Ypenburg (Hageneiland, 2001), firms such as MVRDV were able to combine the despised row house with Koolhaas's conceptual design method, and the Vinex district became 'worthy of the profession'.

Adriaan Geuze also expressed dissatisfaction with the Vinex policy as the "betrayal of the rich Dutch planning tradition. He called the Vinex district too much of a policy map, without a vision and without a connection to the location, in which managers had taken over the role of experts. In his exhibition In Holland staat een huis in het NAi, the message was therefore: we cannot build the next 800,000 homes in the same way. In his own plans for the Vinex, such as Vathorst, he put the integral design task back at the heart of mostly classical block plans.

During the creation of the Vinex policy, for the first time market parties became a serious cooperation partner of the government and project developers the clients of architectural firms. After decades in which the (local) government and the corporations determined the building task, these "market parties" were still suspect. Moreover, the assignments given to architects changed substantially during this period. Whereas in the 1980s a full commission with supervision over the execution was normal, paid according to the SR's fee formula, with the market parties the 87% commission emerged, without the supervision over the execution.

Now such a commission is considered enviably extensive; after all, the architect's involvement in a project has been further and further limited since then. But back then, these limited commissions from market parties were a (sometimes too) big step for many of the 'old guard' of the time. But at the same time the Vinex assignment and new clients gave opportunities to the open-minded new generation to which we belonged.

The assignments from the Vinex were spread across the country and therefore gave us every opportunity to use the differences in identity and context in the design. This fascination with identity is clearly visible in the diversity of the designs. Living and the living environment are the most personal things that we can design as architects: the shell of your 'home', after all, home is where the heart is.

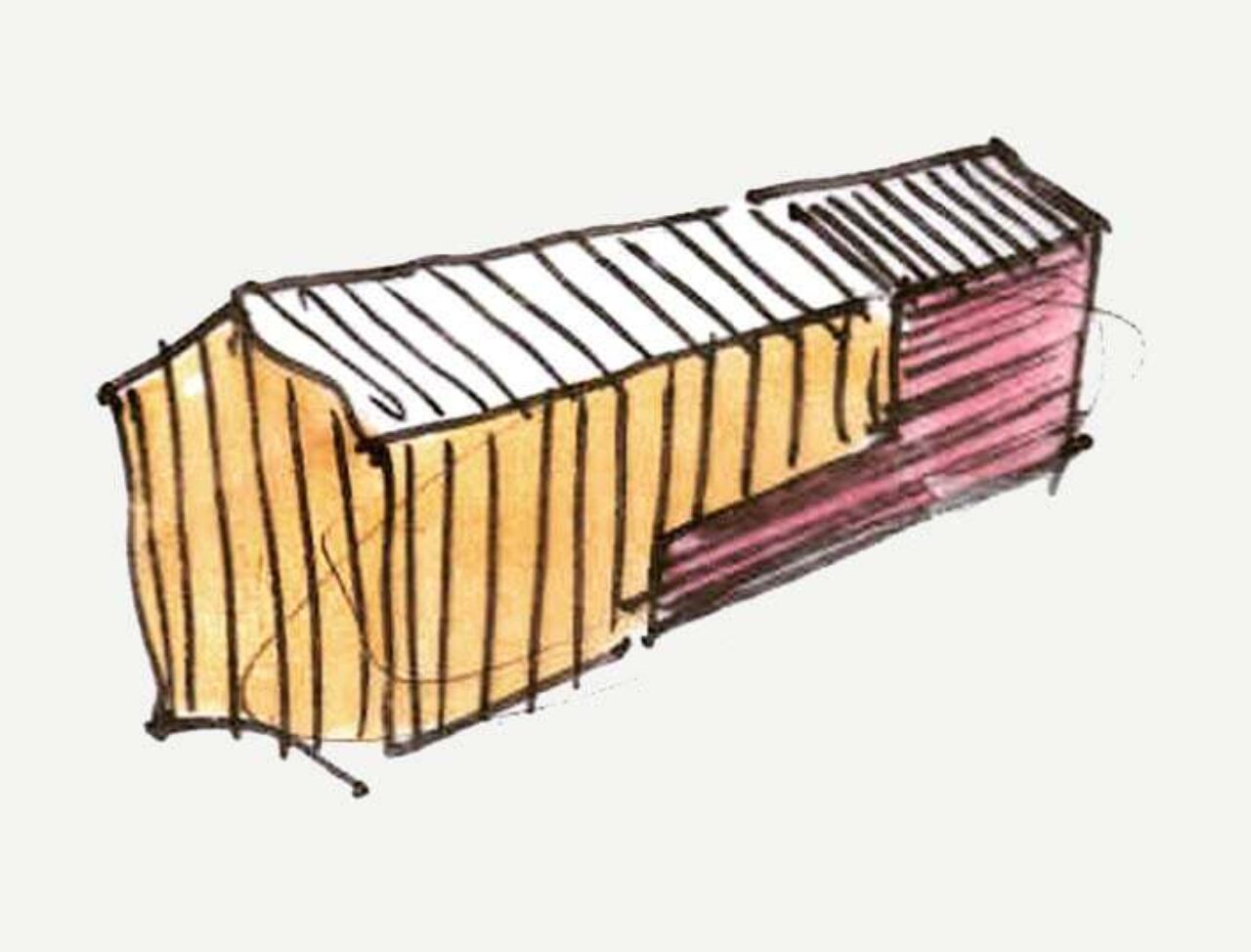

Weidevenne, on the outskirts of Purmerend, is a truly contextual design, both in housing form and architecture, as the identity of the surrounding Waterland radiates through everything: the endless views across meadows and the water everywhere. Wood and brick together form the 'langjaar' here, a reference to the Zaanstreek barn, which was extended lengthwise every year after the harvest. Moreover, in this long, narrow house you don't live 'standard' but 'just right'. Differences in height create a strong relationship with the water and in a harsh winter you can skate from your house into the waterland, a truly Dutch Anton Pieck moment. The caps and the water still provide that same timeless feeling.

All the way on the other side of the country, in Stadshagen (Zwolle), we were looking for precisely the stout scale of the historic fortifications that typify the Hanseatic city of Zwolle. All the houses and apartments in De Rug are bundled into a compact, sturdy and powerful ensemble of brickwork that meanders towards the open water. The green space thus created, with open vistas to the water, was a welcome urban design addition to a homogeneous sea of houses. This urban intervention also gave new preconditions for living. The differences in height, as well as the choice of a narrow beech, produce special, spatial split-level homes, behind a green dike in the landscape. The single-family dwellings gradually change into maisonettes and finally into a header with double apartments, framed in basalt blocks. The rough masonry, which refers to a fortress due to the protruding stones, still makes De Rug a distinctive and timeless design. The artwork Storm King Wall by Andy Goldsworthy provided a strong reference image for De Rug.

Leeuwenveld in Weesp is not a Vinex neighborhood, but for us it turned out to be the end of a period in which we designed large housing locations with mainly ground-level housing on the outskirts of cities. The fact that we made both the urban and architectural design here is visible. Leeuwenveld was closer to the existing city than the Vinex neighborhoods. In the urban and architectural design, the identity of Weesp with its canals and pledges is central. This has created an integral coherence which, despite our fond memories of 'loose' housing projects, transcends the level of the Vinex neighborhood.

The Vinex policy was successful and rapidly became, with its large scale, spatially very decisive for the appearance of the Netherlands. And, more importantly, the Vinex neighborhoods became the home of many. Young families were able to realize their housing dreams en masse, children were born here and grew up in these, in reality, beloved neighborhoods. Ironically, this also applies to architects, who, although they like to embrace urban living in their design conception, are not so different in their own housing requirements from all those 'ordinary' people, who ultimately like to live with their families in a house with a garden in a nice neighborhood.

I myself have gone through a reversal of scale. Having grown up in a 1930s neighborhood on the outskirts of Haarlem, I now live for more than thirty years in the Pijp district of Amsterdam. In that period Amsterdam has changed into a metropolis. Whereas in 1985 there was still talk of depopulation, now densification in the city is the order of the day. The stacked and inner-city housing assignment that we, including LEVS, have been embracing more and more since 2005 is a broadening and deepening of the content, but also a logical consequence of the end of the Vinex. It became the new norm, but there has also been a rapid development in this area. We are now not surprised by 70, 100 or 140 meter high towers in the inner cities. This will radically change our living and lead to new questions and design challenges, on which we will work with inspiration to find the right answers, where identity, housing quality and collectivity come together.